The current global lock-down, put in place to deal with the Corona pandemic, is grinding life as we knew it to a halt. Nobody knows how the world will resume after this crisis. The cynical predict an even bigger divide, the hopeful a stronger social cohesion.

But this is not the first pandemic to have disrupted society. The Black Death for example arrived on European shores around 1347 and returned several times during the decennia to follow.That pandemic ended up killing approximately half of Europe’s population, with no regard for people’s wealth, social standing or religious piety.

Historians argue that the phenomenal loss of lives and the radical disruption of Middle Age Society (social, political and religious) paved the way for the Renaissance (rebirth), a period (14th-16thcentury) of unparalleled ingenuity and productivity in the arts and sciences. The focus shifted from the divine to the human, as the classic Greek philosopher Protagoras noted “Man is the measure of all things”.

But the idea of “Man” was very white and the way black women were depicted in Renaissance art for example, testifies that other cultures were little understood and merely appreciated for their exotic otherness.

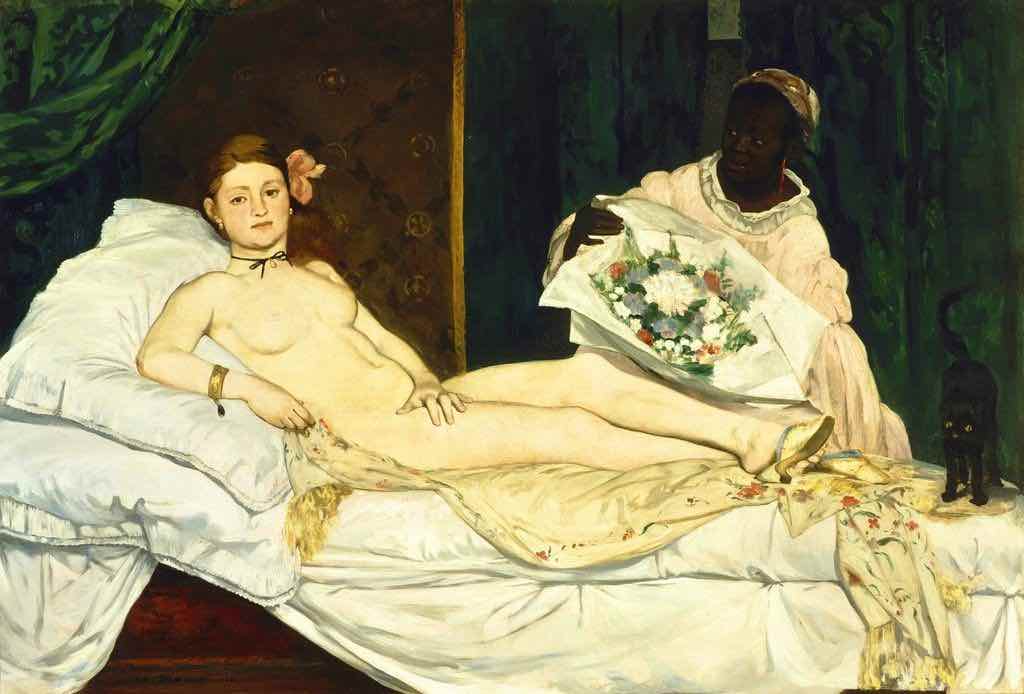

Black female bodies, servants to the wealthy white, seem to be depicted to emphasize the beauty of the milky skinned protagonists. Whilst the nude white female epitomises sensuality and beauty, the black female, often fully clothed, seems devoid of any sexuality or beauty. Black womanhood seems confined to “a space of functional and visual servitude to white beauty”.

As ‘Olympia’ by Edouard Manet from 1863 illustrates, this idea of white superiority became entrenched over the centuries and still persists.

Whilst it is hopeful to know that phoenixes can rise from the ashes of pandemic havoc, it’s our responsibility to ensure that these major inequalities are addressed in the process.

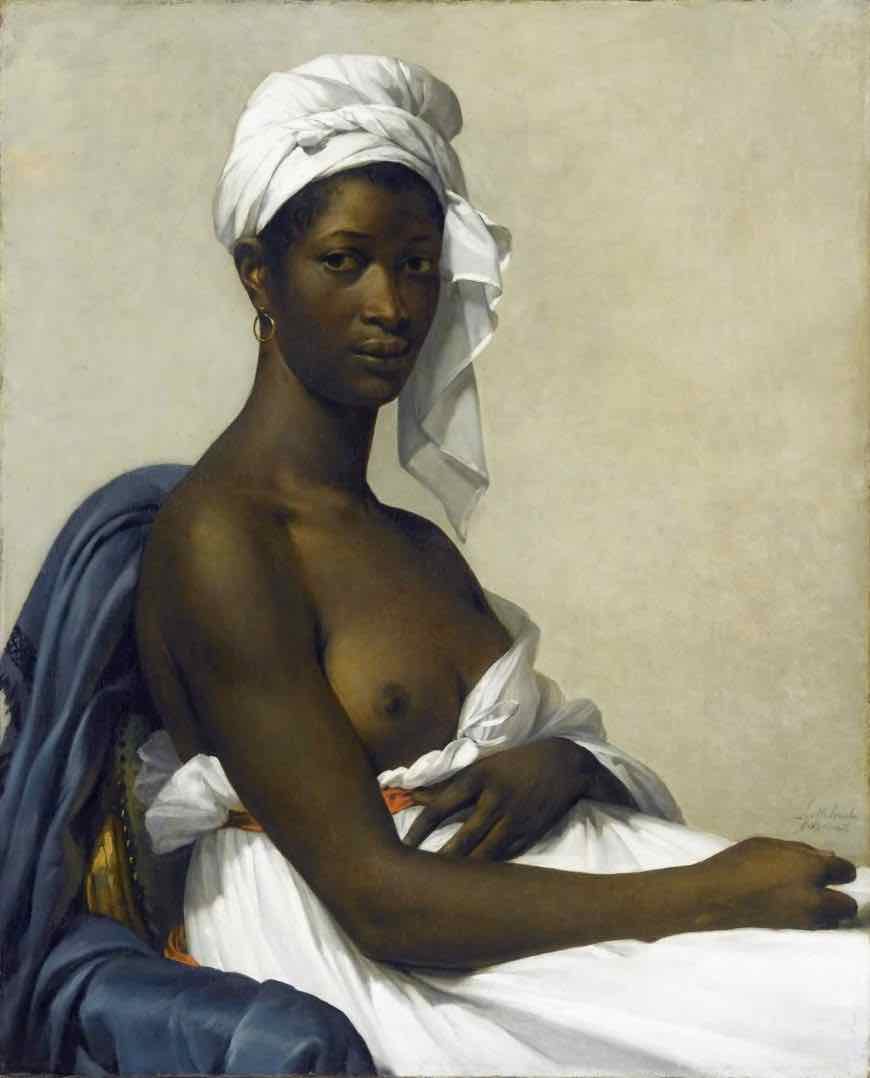

French artist Marie-Guillemine Benoist seems to have done exactly that. In 1800 she portrayed an anonymous woman of African descent in the same way as a well-off white woman would have been painted in those days. And although Portrait of Madeleine (formerly known as Portrait of a negress) was dubbeda “black stain” by the Salon Carrécritic, in conveying the beauty and humanity of the sitter, the painting seems to suggest that anonymous women and women of African descent are to be treated as equals.

(Benoist’s bare breast might have been a critique of the slave trade which was illegal on the French mainland but had still some advocates for reinstating it).

Anna Versteeg