Bathsheba’s Breast

Whilst temporarily confined to my bed with a recalcitrant lower back, I finally got to read “Bathsheba’s Breast” (2002) by Historian James S Olson.

Utilizing women’s voices across the centuries, Olson has created a truly accessible and captivating account of the history of breast cancer, looking at gender dynamics between female patients and male physicians, medical and technological developments, culture, economics, societal changes and politics.

“Breast cancer may very well be history’s oldest malaise, known as well to the ancients as it is to us. The women who have endured it share a unique sisterhood. Queen Atossa and Dr. Jerri Nielsen—separated by era and geography, by culture, religion, politics, economics, and world view—could hardly have been more different. Born 2,500 years apart, they stand as opposite bookends on the shelf of human history. One was the most powerful woman in the ancient world, the daughter of an emperor, the mother of a god; the other is a twenty-first-century physician with a streak of adventure coursing through her veins…” (dramatically evacuated from the South Pole in 1999 after performing a biopsy on her own breast and self-administering chemotherapy)—from Bathsheba’s Breast

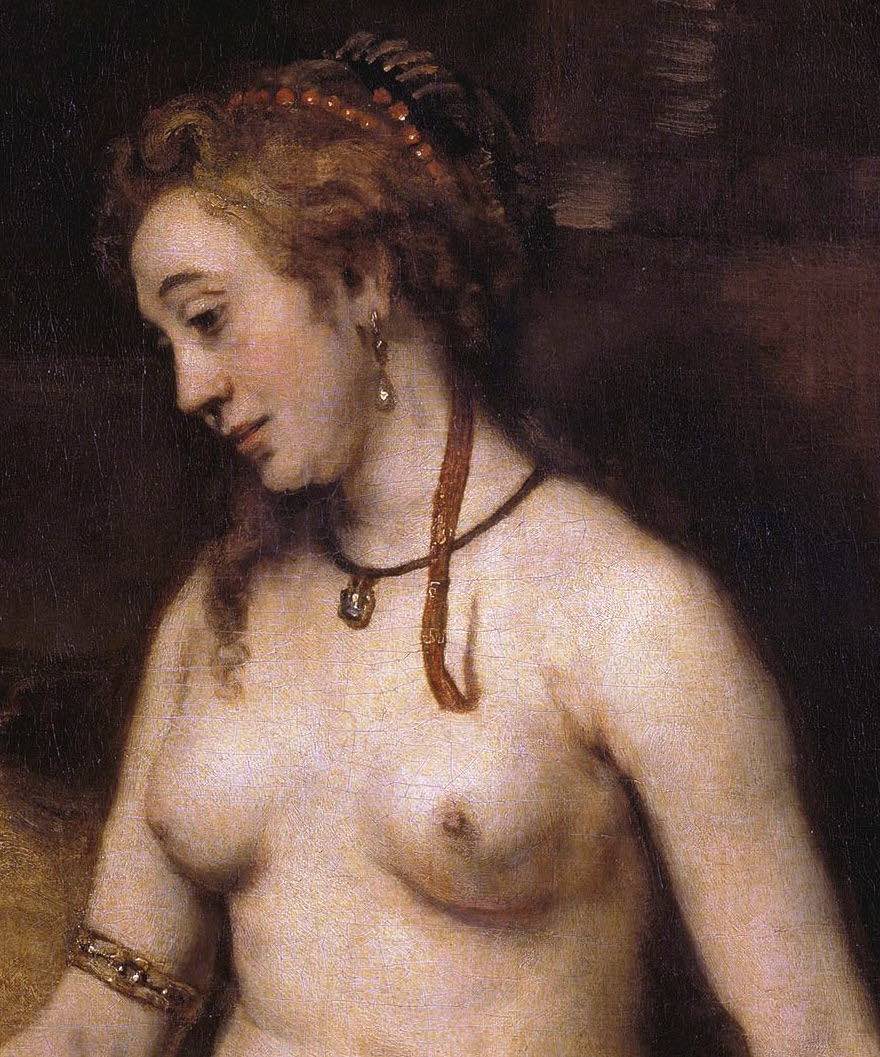

In 1967, an Italian surgeon touring Amsterdam’s Rijks museum stopped in front of Rembrandt’s Bathsheba at Her Bath, on loan from the Louvre, and noticed an asymmetry to Bathsheba’s left breast; it seemed distended, swollen near the armpit, discolored, and marked with a distinctive pitting. With a little research, the physician learned that Rembrandt’s model, his mistress Hendrickje Stoffels, later died after a long illness, and he conjectured in a celebrated article for an Italian medical journal that the cause of her death was almost certainly breast cancer.

Detail of Bathsheba by Rembrandt, 1654

Anna Versteeg